Automatic language translation

Our website uses an automatic service to translate our content into different languages. These translations should be used as a guide only. See our Accessibility page for further information.

The Supreme Court acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation, their land and their leaders. Indigenous peoples have suffered many injustices over the past two centuries. This Court will continue to work with our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to ensure they are properly recognised and treated fairly, and with dignity and respect under the law.

Indigenous tribes possessed the Australian continent for millennia, managing its vast landscape and fragile environment. In R v Lowe (1827), the Supreme Court held that the indigenous inhabitants had the rights and duties of British subjects. English law, however, treated the land as something to be granted, bought, leased and transferred, without regard for the rights of the traditional owners. Unchallenged Executive action and unchecked private licence would see Indigenous people pushed out of traditional lands and prevented from hunting and fishing according to their customs of millennia. In Attorney General v Brown (1847), the Supreme Court ruled that the Crown had original title to all ‘waste land’ after 1788.

British colonisation of Australia, and through it the founding of the Supreme Court, owes much to the operation of criminal justice in Georgian England. Harsh, iniquitous and ineffective at deterring crime, its wide range of capital offences was designed to protect property, rather than public safety. The perceived threat was a criminal class, which burgeoned amid the urbanisation, inequality and squalor of industrialisation. When the futility of public hangings and prison hulks became apparent, and transportation of convicts to North America was no longer an option, the British Government turned in desperation to a penal colony in the Antipodes.

Governor Lachlan Macquarie emancipated many convicts and appointed them to positions in all spheres of life, including the law and medicine. Some of Macquarie’s pardons were overturned, but that did not halt the growth of an increasingly assertive class of freed convicts and their native-born offspring. Opposing Macquarie were the Exclusives; retired officers, free settlers like the Reverend Samuel Marsden, and wealthy pastoralists like John Macarthur. The Exclusives had the pretensions of a landed aristocracy, based on a reliable supply of assigned convict labour. The British Government came to share the Exclusives’ dismay that Macquarie was soft on convicts.

English law arrived with the First Fleet in 1788. The First Charter of Justice (1787) established a civil court and a court of criminal jurisdiction, headed by a deputy judge-advocate and six military officers, many of whom had no legal training. The Second Charter of Justice (1814) created three new civil courts, including the Supreme Court of Civil Judicature. The colony’s first judge was Judge Jeffrey Bent, whom one historian described as ‘vain, pretentious, insolent and un-conciliatory’. Bent refused to allow former convicts to appear as solicitors and heard no cases at all for two years. He clashed frequently with Governor Macquarie, who wrote that ‘the highest law officer in the colony is the root of every faction and cabal that takes place in the colony’.

By the 1820s New South Wales had begun to prosper, but to the British Government this was incompatible with the colony’s function as an antipodean prison; ‘an object of real terror.’ On 5 January 1819 Commissioner John Bigge was appointed to review the colony’s affairs. His third report, Inquiry on the Judicial Establishments of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land, recommended forming a Supreme Court and a Legislative Council. The Imperial Parliament passed the New South Wales Act 1823. The Third Charter of Justice reached Sydney and was proclaimed with the opening of the Supreme Court on 17 May 1824.

Establishment of the Supreme Court and the office of Chief Justice meant that the administration of justice in the colony required an appropriate building. The King Street Courthouse, built between 1820 and 1827, was the first permanent home for the Supreme Court. Its three main buildings remain in operation today: the original courthouse on the corner of King and Elizabeth Street; the Registry on Elizabeth Street (built 1859); and the St James Road Banco Court (built 1894-96). By the 1830s use of King Street Courthouse was growing rapidly.

In response to the overcrowding and chaotic state of King Street Courthouse, the construction of a new criminal courthouse in Darlinghurst was initiated. In 1835 Governor Bourke directed the design of the courthouse to be situated outside Sydney Town, upon the hill opposite the new gaol, for convenient prisoner access and to separate criminal matters from civil matters in the city. Criminal trials, however, continue in King Street to this day.

By the early 1820s, exports of wool to Britain began to generate immense wealth. Land west of the Great Dividing Range was granted to white pastoralists with no recognition or regard for the traditional rights of Aboriginal people. Between 1820 and 1824, the white population increased tenfold in the Bathurst region, from 114 to 1,267. There, conflict between settlers and the Wiradjuri people escalated and on 14 August 1824 Governor Brisbane declared martial law. Aboriginal leader Windradyne led his warriors in a guerrilla warfare campaign, attacking isolated farms. Settlers responded with mounted reprisal raids and mass poisonings until martial law was repealed on 11 December 1824.

In two landmark cases, the Supreme Court considered whether English law would apply to Aboriginal people. In R v Ballard (1829), Forbes and Dowling acknowledged the absence of jurisdiction over, and found this it would be unjust to hold, Aboriginal people accountable under English law for crimes committed against other Aboriginal people. In R v Murrell (1836) Justice Burton (with Forbes and Dowling agreeing) reversed the position in Ballard and found that the Supreme Court did have jurisdiction over disputes between Aboriginal people and that there was no distinction in law between persons living in the colony.

On Sunday, 10 June 1838 an armed posse of stockmen rode to a cattle station near Myall Creek, where they slaughtered more than 28 Wirrayaraay men, women, and children. Eleven men were arrested. Evidence given at their trials before the Supreme Court provides a rare contemporaneous account of a brutal episode in our history. In summing-up the case, Chief Justice Sir James Dowling told jurors that ‘a most grievous offence has been committed; … the lives of near thirty of our fellow creatures have been sacrificed’. The jury deliberated for no more than fifteen minutes before acquitting the accused.

Undeterred, Attorney General John Plunkett secured a fresh arraignment for seven of the accused on 27 November 1838. The evidence at the second trial was similar, but a different jury delivered the verdict of guilty in relation to the murder of one male Aboriginal child. On 5 December 1838 Justice Burton pronounced the death sentence for each of the prisoners. They were executed on 18 December 1838. The Myall Creek trials proclaimed formal equality before the law, but in reality, Aboriginal people received no recognition and very few rights or protections until the late twentieth century.

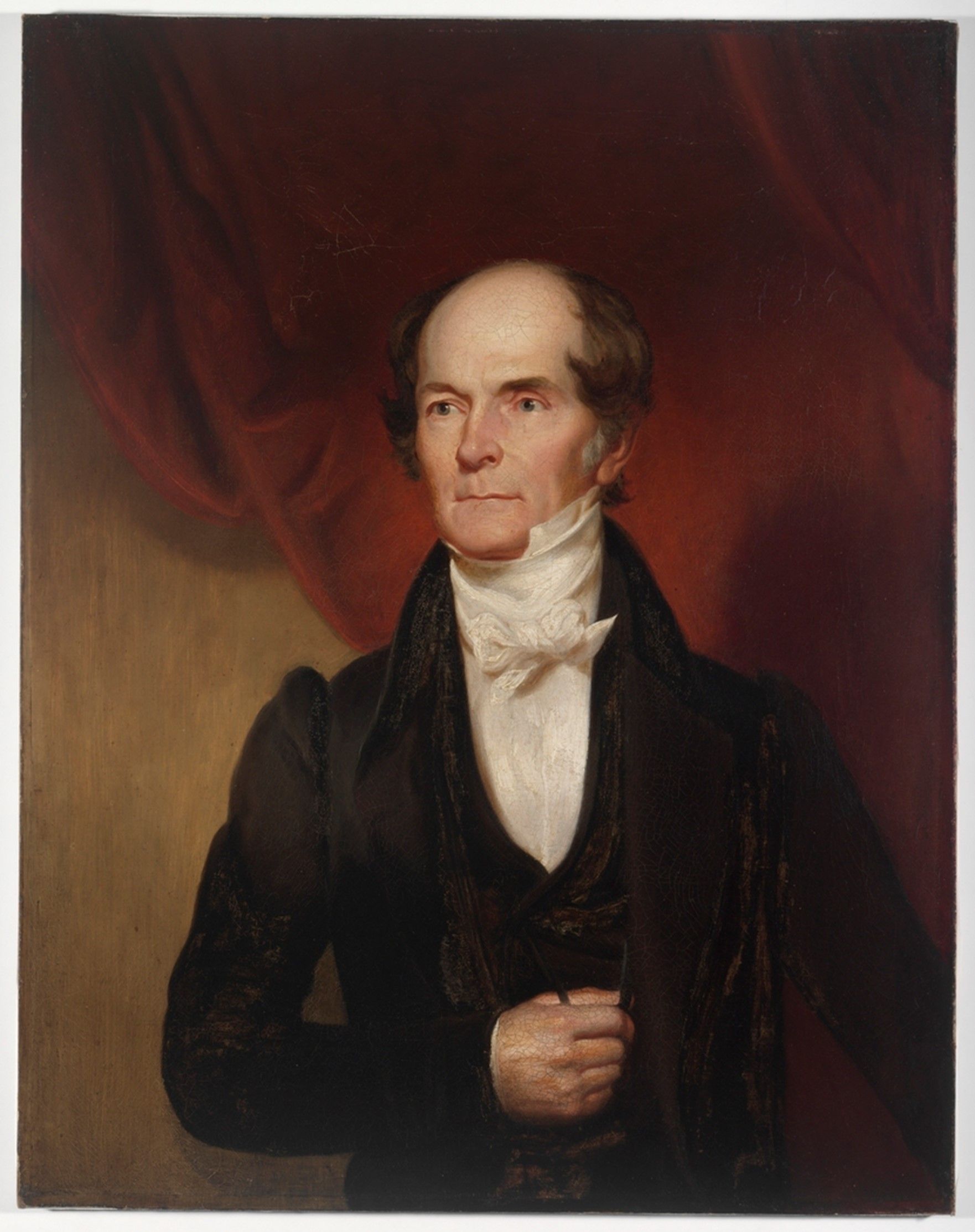

Francis Forbes was called to the English Bar in 1812 and served as Chief Justice of Newfoundland from 1816 to 1822. While on leave in London in 1822, he helped the Colonial Office to draft the New South Wales Act 1823 and accepted an appointment as the inaugural Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court. Under the Act, Forbes was also a member of the Legislative Council and had authority to declare draft legislation to be repugnant to the laws of England – effectively a veto. This was destined to mire him in political controversy. Nowhere was this more pronounced than in his conflict with Governor Darling over revocable licensing provisions of the Newspaper Regulating Act. Forbes was renowned for his pragmatism and even temperament, but his heavy workload and incessant conflicts with Darling and others caused his health to suffer. Forbes was knighted in April 1837 and retired on 1 July 1837. He died on 8 November 1841 at Leitrim Lodge in Newtown, Sydney.

James Dowling arrived in Sydney in February 1828. Like Forbes, Dowling’s first years on the Bench of the Supreme Court were shaped by libel cases, ‘pregnant with political excitement and party feeling’, between Governor Darling and the colony’s scurrilous newspapers, the Monitor and The Australian. He succeeded Forbes as Chief Justice in 1837, but like his predecessor, the incessant demands of judicial office, service on the Legislative Council and ongoing financial difficulties combined to exact a toll on his health. On 27 June 1844 Dowling collapsed while on the Bench and died three months later. Renowned for his meticulous record keeping, he was responsible for publishing the colony’s first set of law reports, which documented the early work of the Supreme Court and the development of a distinct Australian common law.

We acknowledge Aboriginal people as the First Nations Peoples of NSW and pay our respects to Elders past, present, and future.

Informed by lessons of the past, Department of Communities and Justice is improving how we work with Aboriginal people and communities. We listen and learn from the knowledge, strength and resilience of Stolen Generations Survivors, Aboriginal Elders and Aboriginal communities.

You can access our apology to the Stolen Generations.